Sorry I’ve been blogging less. Illness sucks. But please enjoy this essay that I wrote for the BookForum Dystopia issue back in summer 2010. A few things in it are a tad out of date, obviously, but the basic ideas still seem pretty sound to me.

Teens and Dystopias

Literary dystopias flourish at the extremes of social control: the tyranny of too much government, the chaos of too little. Every 1984 or Fahrenheit 451 is balanced by a Mad Max or A Clockwork Orange. Or to put it simply, dystopian literature is just like high school: an oscillation between extremes of restraint.

Teenagers, of course, read dystopian novels in vast numbers. (As I write, Suzanne Collins’ post apocalyptic dictatorship novel, Hunger Games, has entered its eighty-first week atop the NY Times Chapter Book list.) This should surprise no one. Within school walls, students have reduced expectations of privacy (New Kersey v. TLO, 1980), no freedom of the press (Hazelwood v. Kuhlmeier, 1983), and their daily reality includes clothing restrictions, rising and sitting at the command of ringing bells, and an ever-increasing amount of electronic surveillance. But a few footsteps away from these 1984-like subjugations, the teenage world becomes Mad Max—warring tribes, dangerous driving, and unfortunate haircuts.

Teenagers’ lives are defined by rules, and in response they construct their identities through confrontations with authority, large and small. All this leaves teens highly interested in issues of control.

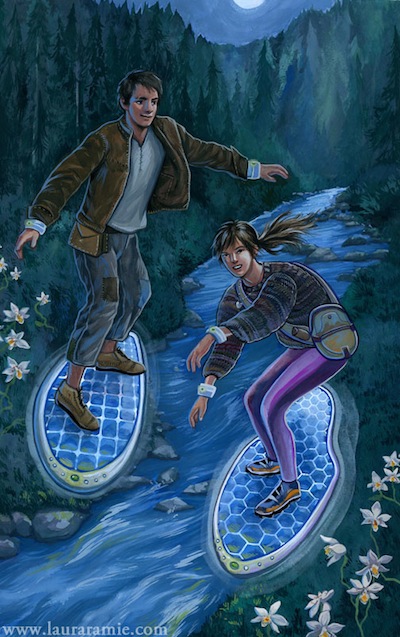

When I sat down to write the Uglies series in 2003, I didn’t intend to address these matters directly. I thought I was writing a somewhat nostalgic science fiction trilogy about body image and hoverboards. But a few million copies and roughly ten thousand pieces of fan mail later, I feel qualified to speak about teenagers and dystopias.

First a quick synopsis: Uglies is set three centuries after an “oil bug” has destroyed our present-day economy and all but erased our species. The descendants of the survivors live in isolated city states, ambiguous utopias whose citizens enjoy post-scarcity technologies and rigid government control. The title derives from this society’s coming-of-age tradition, in which teenage “uglies” undergo full-body plastic surgery to become “pretties,” simultaneously adult and beautiful. (And yes, there is a Twilight Zone episode along these lines, and about two dozen novels and short stories as well. As I said, this series was meant to be nostalgic.)

The protagonist of the trilogy, Tally Youngblood, is most notable for her shifting identities. By turns she takes the roles of vandal, government informer, outcast, runaway, prisoner, hedonist, enforcer, self-mutilator, and full-throated revolutionary. Her personality is reprogrammed several times, her memories frequently erased, her allegiances always suspect.

And yet the most common line in my fan mail is simply, “I am Tally.”

I think this is because teens recognize all the roles that Tally takes on. Schizophrenia, switching sides, and even betrayal (both of allies and of self) are natural responses to being bounced between extremes of control.

During my last book tour in the UK, the big tabloid story was a grandmother barred from a shopping arcade for wearing a hoodie. The management sheepishly explained that it was just a policy, and clearly not one aimed at grandmas. They didn’t have to say at whom it was aimed. After all, five little kids in a shop is cute. Five adults, good business. But when five teenagers gather, it’s time to make an arbitrary rule, or better yet to install a high-frequency sound device to drive them out.

Whatever teens embrace—whether it’s black hoodies, rap, texting, file-sharing, hoverboards, or fictional vampire boyfriends—is soon decried as a threat to civilization. And trust me, teenagers notice this adult discourse going on around them. They know they live in occupied territory.

They also realize that these social panics and excesses of control do little to protect them from their real problems. Censoring the school paper (or internet feed) doesn’t protect anyone from bullying, or agonizing over every physical imperfection, or from sexual predators (who overwhelmingly come not from the internet but from within teens’ own families). Like Tally’s world, ours is primarily concerned with surfaces, using plastic surgeries for real diseases. Being relative newcomers, teenagers see through this chicanery better than their elders, but at the same time possess fewer skills and resources to escape its power.

So they wind up with the worst of both worlds—too much government and not enough. Is it any wonder, then, that dystopian novels appeal to teens, as do vandalism, cutting, fast cars, shifting identities, unfortunate haircuts, and black hoodies? Next time you read a dystopia that strains belief, just think back to high school, and it won’t seem so far fetched.

Thus endeth the essay. Hope you enjoyed it.

And hey, do you want to help provide classroom copies of Uglies to a junior high school in the Bronx? Just click here to find out how. (Even if you’ve got no money, voting for and “liking” the project helps too!)

Oh, and Keith did an illustration for the essay as well. Check it out!